Update: On the 28th of April 2024, Google decided to finally pay a dividend. It’s no longer an NFT. So when reading “Google” below, replace it in your mind with a generic “non-dividend paying stock”

Dividends are not irrelevant. They are the REASON for a stock’s existence. Those who insist on the irrelevance of dividends, need to ask themselves a simple question:

Would you hold Google stock if you could never sell it?

Google famously doesn’t pay dividends. So let’s say tomorrow Google announces that at the end of the month, it’s delisting from the NASDAQ, and won’t re-list on any other exchange, making it impossible for you to sell. What would you do with your stock? Would you sell it, or keep holding it?

If your answer was “I will keep my Google stock, even if I could never sell it”, then congratulations. You are a genuine investor, and you should feel proud of yourself. Please feel free to tell me I’m an idiot in the comments section.

If, however, your answer was “I will sell my Google stock ASAP”, then you are NOT a genuine investor in Google. You are a bagholder, trying to unload a glorified NFT on the first gullible idiot, foolish enough to take it off your hands.

Now let’s ask the same question about your house.

Would you keep your house if you could no longer sell it?

And the answer will be – overwhelmingly, I hope – yes! Because a house has intrinsic value regardless of whether you sell it or not. It either provides you with an explicit cashflow via rent received, or an implicit cashflow, via the rent you save from living in it.

That’s the core of my thesis, which I expand below. If the only value of your stock is the price at which someone else is willing to buy it, then what you have on your hands is a “greater fool” asset. NOT an investment. It is speculation. Like Bitcoin, NFTs, and even gold, a stock without dividends has no intrinsic value. At least a monkey JPEG is funny. Google stock is not even that.

Below, I take each argument in favor of the “Irrelevance of Dividends”, and bust them one by one:

Table of Contents

- My Skin in the Game

- I am NOT a “Dividend Investor”

- Investing Using the Gordon Equation

- But What if the Company Starts Paying Future Dividends?

- The “Dividends are Not Free Money” Fallacy

- A False Dichotomy – No Company Pays out 100% of Earnings

- Yes, Dividends are Less Tax-Efficient

- Why Stock Buybacks Aren’t Good Enough

- Dividends are Never Cut as Much as the Price Falls

- “Total Return” is NOT All that Matters

- Stocks are Not the Same as Companies

- Berkshire Hathaway – the Elephant in the Room

- We Need to EXTRACT Money From a Company – Not Sell Shares

- How Companies Waste your Money: Why We Need Dividends

- Dividend Growth: The Factor Investing Distraction

- The “Anti-Dividends” Fanaticism

- Dividends are Better from a Behavioral Standpoint

- With Dividends Stock Price is Irrelevant

- Conclusion

My Skin in the Game

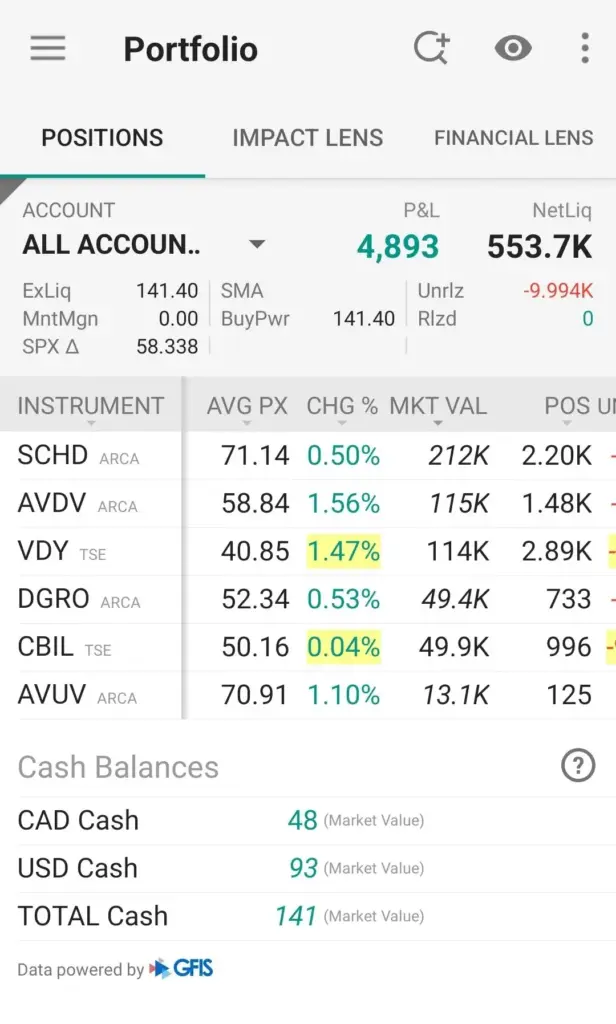

First, allow me to demonstrate that I’m not all talk. I believe what I’m saying and I structure my portfolio accordingly. Here is a screenshot of my portfolio as of the 10th of October 2023:

Here are my estimated annual dividends:

As you can see, I’m not reaching for the highest yield, and I don’t have to. Furthermore, I’ve been arguing in defense of dividends for years. These are my deeply held convictions. I’m not trying to sell you anything or get you to follow me, or whatever. My goal is to spread awareness and to educate the public, nothing more.

I am NOT a “Dividend Investor”

Despite the title of this post, and despite my disdain for non-dividend paying stocks, I don’t consider myself a “dividend investor”. I am, in fact, just a regular investor. I invest in things that have monetary value, and which derive their value from their cash flow.

Why cashflow?

Because all financial instruments are valued according to their cash flow. What gives a house value? The rent that you can derive from it, or the rent that you save by living in yourself. What provides a bond with value? The coupon payments. What gives mortgage-backed securities their value? Again, the risk-adjusted cash flow.

What gives a stock value? That’s right. Dividends.

The concept of valuation being tied to cashflow is a fundamental law of financial instrument analysis. Cashflow is what gives a stock intrinsic value. Without cashflow, a stock has zero value. And yes, that means that I value Google stock at 0. The author William Bernstein – whose books many will recommend for investing – has this to say about cashflow.

The real value of your assets is not the number on your brokerage statement, but the stream of income it provides.

(Bernstein, W.J. [2002]. The Four Pillars of Investing: Lessons for Building a Winning Portfolio. New York: McGraw-Hill.)

Remember that. What we are interested in is a stream of income. Without that stream of income, your portfolio has no value.

Yield is NOT the Only Thing that Matters

Another mistake that people who try and “debunk” the relevance of dividends make, is assuming that just because I require dividends as proof of value, it means I must be trying to maximize my dividend yield. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Several companies that I hold via ETFs have dividend yields of ~2%. A far cry from the 8% yields that die-hard dividend investors sometimes look for. This is another reason why I don’t consider myself a “dividend investor”. Remember the Gordon equation? That equation has two parts. The first is the yield, and the second is the growth of that yield. It’s fine if a company has a low dividend yield, as long as we have indications that it continues to grow it to make up our expected ROI.

So, for example, if we’re targeting an average of 8% returns, and a company has a 3% yield, we need to see and expect a growth in yield of 5% per year on average. The Gordon equation is deadly simple, and there’s no escaping its math. Microsoft has a very low dividend yield, but its dividend growth rate is so high, that it more than makes up for it and achieves a very significant ROI.

I Invest Only in ETFs, No Individual Stocks

Yet another assumption people make about this approach is that we need to choose individual stocks for their dividends. This is utterly false. There’s zero need to expose yourself to idiosyncratic risk associated with single stocks. The normal principles of investing apply to a dividend strategy.

High diversification, low costs, and the more companies in your portfolio, the better. None of this is anything new.

Investing Using the Gordon Equation

The Gordon equation is like a fundamental law of finance. Referring once again to William Bernstein, here’s what he had to say about it:

The Gordon Equation is as close to being a physical law, like gravity or planetary motion, as we will ever encounter in finance. It can predict the long-term (30 year) expected return of the market.

(ibid)

So what is this magical equation? When you abstract and simplify all the complex math behind it, the Gordon equation comes down to a simple line:

Expected Returns = Dividend Yield + Dividend Growth

Yes, it’s that simple. Take the existing dividend yield, add the dividend growth rate, and you get your expected returns. If you’re interested in a more theoretical understanding, you can start with this paper explaining how it works. Wikipedia also has a good page explaining the dividend discount model, on which the Gordon equation ultimately rests.

Now, of course, estimating the dividend growth of a stock or ETF is an exercise in judgment. But at least you have objective data about past dividend growth. And if you buy an ETF filled with dividend growers, they’re not all going to stop paying their dividends at the same time.

I evaluate every single one of my investments against the Gordon equation. This means that if a stock pays no dividends – like Google – then I treat it as a worthless NFT.

TIPS Bonds: Proof that the Gordon Equation Works

If you’ve ever thought about protecting yourself against inflation, you might have looked at TIPS bonds. These are treasuries whose principle and coupon payments adjust based on inflation. Pretty cool, right? However, their yield is always lower than treasuries – wonder why?

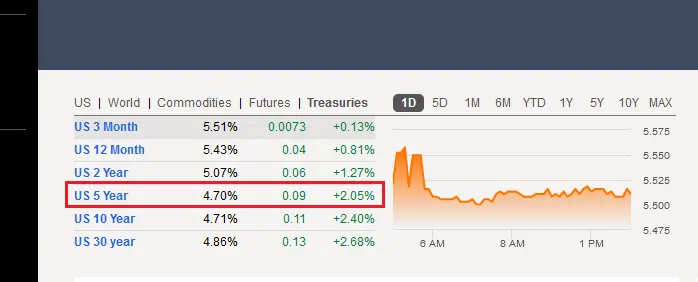

Here is the current yield on 5 and 10-year treasuries:

Source: Seeking Alpha

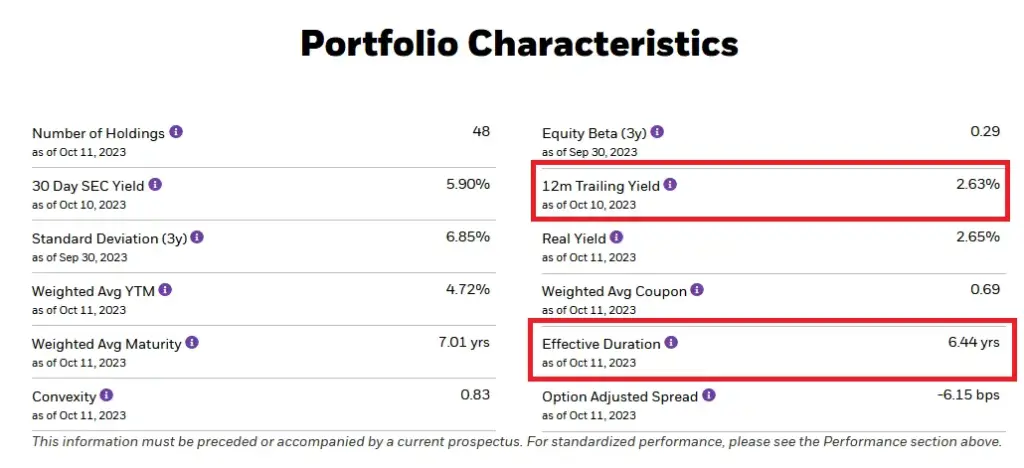

So treasuries are currently yielding 4.70%. But the BlackRock TIP ETF, which consists of TIPS treasuries with an average duration of 6.44 years is currently yielding just 2.63%:

Source: iShares TIPS Bond ETF Fact Page

Note: The TIP ETF skips payments often, which is why the 30-day SEC yield is misleading.

So why the difference between the two? The reason is that TIPS bonds grow their yield by the inflation amount as measured by the CPI. And the difference in yields is the market expectation of long-term inflation! So in this case, the market is expecting an inflation of:

Inflation = 10-year yield – TIPS yield = 4.70% – 2.63% = 2.07%.

It’s actually a bit higher than this because the 12m trailing yield is lower than 2.07 , thanks to rising interest payments throughout the year due to Fed hikes, but you get the idea. Looking at this, the market is expecting long-term inflation to settle around ~2.5%. This is a well-known concept known as the 10-year Breakeven Inflation Rate. This rate is a direct consequence of the math of the Gordon equation. It’s an ironclad rule.

Why Fixed Income is no Substitute for Dividends

With interest rates at a high point right now, and with bonds finally being useful, people look at the measly 3-4% dividends that companies issue and wonder why even bother? Why settle for a lower return with risk than short or long-term government bonds that have no risk?

The reason, once again, is the Gordon equation.

The bet is that these companies will increase their dividends. When you add the current yield to the projected growth in that yield, you get the expected long-term return of the asset class. What’s the growth in the yield of bonds? (absolute numbers, not percentages). Zero. And that’s why dividend stocks are still worth it compared to government bonds.

The Gordon equation. Never, ever forget the Gordon equation.

But What if the Company Starts Paying Future Dividends?

One possible objection you might have is that while a company isn’t paying dividends now, doesn’t mean that it won’t start paying them in the future. When that happens, the theory goes, it will make up for all the dividends it has skipped paying so far.

Color me skeptical.

If a perfectly profitable company like Google doesn’t pay dividends, I sincerely doubt it can ever disgorge sufficient cash in the future to make up for all the dividends it could have been paying all this while. Right now, Google can jolly well afford to pay a measly 3% dividend, but it chooses not to. Whatever future dividends it may pay in the future (I very much doubt it), I don’t think it’s going to make up for these lost years.

Investing by estimating the future is hard enough, and risky enough as it is. Trying to factor into your calculations, the likelihood that a company will start paying dividends at some uncertain point in the future, then estimating how much the dividend will be and how much it will grow is a feat that will defeat the most determined crystal ball. Investors who try and predict these uncertain variables are deluding themselves. It’s far more likely that the company will shut shop and die before you ever see a cent of disbursements.

A company might or might not pay dividends in the future. That means additional risk. And investors are not compensated for this additional risk. In all the analyses of Google’s risk factors, I never see a factor saying “Google might never pay dividends”. Many investors treat this as a feature instead of a bug. They’re so afraid of taxation, that they’re willing to hold valueless assets. Talk about the tail wagging the dog!

The “Dividends are Not Free Money” Fallacy

Yeah, no shit! This is the go-to line of the “dividends are irrelevant” crowd, as they play what they think is the trump card to end all arguments.

Except that it’s a strawman. Not a single person who has the slightest knowledge about how finance works is ever under the delusion that dividends grow on trees. It’s kind of obvious that dividends come from a company’s assets, right? Or did they believe that those who want dividends think the money “magically” appears out of nowhere?

Retaining and Paying a Dividend are NOT Equivalent

Even though dividends are not “free money”, the choice to receive and re-invest dividends is not the same as the company retaining 100% of its earnings. This is the most prevalent myth perpetrated – unknowingly – by those who claim that dividends are irrelevant.

Those arguing against the relevance of dividends provide the following argument. Let’s say a company’s stock is worth $10. In scenario A, it provides a $1 dividend. In scenario B, it retains its earnings. According to them, the two scenarios are equivalent because of the following math:

Scenario A – with a dividend

Total value = Dividend + (Stock Price – Dividend)

= $1 + ($10-$1) = $10

Scenario B – without a dividend

Total value = Stock price = $10

In other words, the total return is the same because the value of your stock drops by $1 after issuing the dividend (which is paid from the company’s assets). So according to them, this is like transferring money from one pocket to the other. Ben Felix – who has become famous, thanks to his well-known Youtube video on the “Irrelevance of Dividends” (more on that below) – had this to say on his Twitter feed:

But Ben Felix and others who repeat the above sentiment are wrong. While the math for the immediate stock price + dividend is the same because the dividends come out of the stock price, the difference behind the scenes is very large.

Re-Invested Dividends Buy Proven, Existing Cashflows

When you use your dividends to purchase additional shares in a company, you are purchasing more of the same, proven cashflow that the company has already demonstrated it can pull off. There’s no speculation. Mind, I’m not saying that dividends are guaranteed and that the company won’t cut them in the future. But the company has shown that it can generate the cashflow it already has, and you are using your dividends to buy more of the same.

In other words, you are using your dividends to purchase another tap, compared to retained earnings, where the company only promises to grow the size of the existing tap.

Each time you re-invest your dividends, you are purchasing another tap that already exists.

Retained Earnings are Only a Promise of Future Growth

When a company retains its earnings, it’s making the following promise to you:

I will invest this money into the company to generate at least the same returns as the one I’m generating now, if not more. These earnings will be in addition to my existing operations.

The last part is important. The company is promising to grow its business at an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) that is at least the same as what it is currently generating. That growth hasn’t happened yet. It is a speculation. It may never happen. There’s a good chance that the company will fail to generate higher returns on its retained earnings than what it is currently generating.

In general, I don’t believe that magical, revenue-growing opportunities are just randomly lying around in which companies can easily invest their retained earnings at a higher IRR than their already existing cashflow machine.

If you think of a company as a tap from which money flows, then by retaining its earnings, a company is promising to increase the size of that tap.

How much faith do you have in the capacity of human managers to consistently grow the rate of a cashflow? Do you think that they’re all-wise and super-efficient? I don’t. Companies suffer from an exaggerated sense of their own importance and capabilities and routinely overestimate the IRR they can generate from new investments.

Retained earnings and dividends are only equivalent in the moment. It’s like saying that money in a current-account with no interest is the same as money invested in the stock market because they both have the same value in the present.

Will the retained earnings live up to the promises of the company? Will it generate a rate of return more than what the company is already generating? Who knows? It’s a risk. Are you getting compensated for that risk? No.

But Still – Earnings are Only a Means to an End

There’s no denying that many companies can indeed increase their earnings rate by re-investing their dividends. Not all, but quite a few. It’s important to realize, however, that company earnings are not the goal. Money returned to shareholders is the goal. Earnings mean nothing to shareholders, and selling your stock is merely transferring money from one shareholder to another.

In the end, it doesn’t matter how much earnings grow. What matters is how much money leaves the company and comes into the hands of shareholders.

A False Dichotomy – No Company Pays out 100% of Earnings

Those who argue against the relevance of dividends create a false dichotomy. They present their arguments as one of two options:

- A company retains ALL of its earnings

- A company pays out ALL of its dividends

In reality, cashflow-rich companies will never pay out all their earnings as dividends. Healthy companies maintain a payout ratio of less than 60% – namely the percentage of earnings paid as dividends. This leaves a very healthy chunk of change to re-invest into the company to chase that magical extra IRR that investors seem to believe is just lying around for the taking. Fine! Just because a company pays a dividend doesn’t mean it won’t invest in its growth. And if that extra growth comes to fruition, it too will be paid out as dividends.

Yes, Dividends are Less Tax-Efficient

I won’t debate this one. Yes, you will most likely be taxed on your dividends. Some countries, like Canada, give extremely favorable treatment to Canadian dividends, so you might be impacted to a greater or a lesser degree depending on where you live. In most countries, dividends – at least those generated in your home country – are taxed quite favorably, and often at the same rate as capital gains. Nonetheless, there’s no denying that they are taxed in one way or another, while capital gains are not.

The question then becomes, are the taxes worth it? For me, knowing that I’m buying something of value is worth the additional taxation. Yes, your unrealized capital gains are safe from being taxed. But at the same time, you are holding worthless assets that don’t generate a cashflow. If I need to pay tax to hold assets that have value, then so be it. I’m not going to force myself to make poor investing decisions by buying something I consider worthless, simply to avoid taxes. The tail cannot wag the dog.

Most importantly, nothing comes for free. If you want to hold real investments, then you must pay the tax for the cashflow. Saving tax is a horrible reason to hold junk that pays nothing. Having said that, I can already hear the objections forming on the lips of the “dividend irrelevance” crowd.

Why Stock Buybacks Aren’t Good Enough

Stock buybacks are supposed to be the perfect form of returning money to shareholders. After all, they increase the price of the stock without any taxation event! Buybacks appear to be the magic pill that forever puts dividends in the shade. Why would you waste money on giving a dividend, when you could purchase back your own stock? Well, here’s why buybacks are a terrible alternative to dividends.

Dividends vs Buybacks: Investing vs Speculation

I will show, how buybacks encourage short-term thinking by company executives whose compensation depends on the stock price and stock-related metrics like EPS. Buybacks encapsulate the fundamental difference between investing and speculation. Speculation concerns itself with price movements, while investing concerns itself with cashflows.

More on that below.

Buybacks Reward Sellers and Often Penalize Existing Shareholders

I find it a cruel irony that by purchasing its own stock, a company is rewarding those who sell their shares and are no longer investors, while existing investors are left with paper gains that can evaporate in the wind. Particularly when the impact of the buybacks is mitigated by stock dilution in the form of stock-based executive compensation. The only ones who win in that scenario are those who sold out of the company, and the executives.

Apparently, I’m not the only one who thinks this. I have my problems with Buffet’s policy on Berkshire dividends, but in this matter, his views are my own. In Buffet’s 1999 letter to shareholders, he had this to say:

Now, repurchases are all the rage, but are all too often made for an unstated and, in our view, ignoble reason: to pump or support the stock price. The shareholder who chooses to sell today, of course, is benefited by any buyer, whatever his origin or motives. But the continuing shareholder is penalized by repurchases above intrinsic value. Buying dollar bills for $1.10 is not good business for those who stick around.

Letter to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Inc – 1999

Dividends, on the other hand, are a direct reward to long-term shareholders who are incentivized to keep holding the stock to reap its benefits. If they sell, they stop receiving those benefits. Why should a company provide liquidity to those who want to sell their shares?

Buybacks Benefit Company Executives More than Shareholders

Further down, I discuss the Modigliani-Miller theorem, and explain why it fails due to the “agency problem”. Namely that we can’t assume that what’s good for the shareholders will also be good for company management. Stock buybacks are so popular because they benefit executives in the company whose compensation is based on stock options and hitting EPS targets.

In a study for the Harvard Business Review titled “Profits Without Prosperity: How Stock Buybacks Manipulate the Market, and Leave Most Americans Worse Off“, William Lazonick makes the following point:

In 2012 the 500 highest paid executives named on proxy statements averaged remuneration of $24.4 million, with 52% coming from stock options and another 26% from stock awards. With ample stock‐based pay, top corporate executives can gain from boosts in stock prices

Lazonick, W. (2014). Profits Without Prosperity: How Stock Buybacks Manipulate the Market, and Leave Most Americans Worse Off. Paper prepared for the Annual Conference of the Institute for New Economic Thinking, Toronto, April 10-12, 2014 (p. 2).

And this:

The only plausible reason for this mode of resource allocation is that the very executives who make the buyback decisions have much to gain personally through their stock-based pay.

(ibid, p. 13)

Executives are also often compensated based on the company hitting certain EPS targets, which makes them purchase shares even when it makes no sense:

…for the 500 highest paid corporate executives…total remuneration…was increasingly in the form of restricted stock awards that require the company to attain EPS targets.

(ibid, p. 14)

In another paper titled “Stock repurchases as an earnings management device”, Hribar, Jenkins, & Johnson write:

We find a disproportionately large number of accretive stock repurchases among firms that would have missed analysts’ forecasts without the repurchase. The repurchase-induced component of earnings surprises appears to be discounted by the market, and this discount is larger when the repurchase seems motivated by EPS management

(Hribar, Jenkins, & Johnson, 2006)

Bottom line: There is ample evidence that stock repurchases are overly utilized to meet EPS targets to confirm with analyst expectations, to pump stock prices for enhancing executive pay and stock-based compensation.

But in theory, it should still be fine, right? Dividends or stock repurchases are all the same thing! Nope.

Stock Buybacks are Most Often Inefficient

Basic common sense will tell you that stock repurchases only make sense when the share is trading at below its intrinsic value. The same principles of investing apply when purchasing your own shares, as when you buy those of another company. Ideally, a company is in a better position to know the intrinsic value of its shares, so wouldn’t companies buy back their shares at attractive prices? But this doesn’t happen.

If the thesis is true, then share buybacks should increase during recessions and lowered prices, and decrease during bull-runs, right? After all, if share prices are depressed beyond reason, then it’s the perfect time to pick up your own shares on the cheap. The truth is that the reverse happens.

executives often claim that buybacks are financial investments in undervalued shares that signal confidence in the company’s future as measured by its stock-‐price performance. But as we have seen, over the past two decades major US companies have tended to do buybacks in bull markets and cut back on them, often sharply, in bear markets

Lazonick, W. (2014). Profits Without Prosperity: How Stock Buybacks Manipulate the Market, and Leave Most Americans Worse Off. Paper prepared for the Annual Conference of the Institute for New Economic Thinking, Toronto, April 10-12, 2014 (p. 11).

This is the reverse of what is supposed to happen. Companies routinely overpay for their stocks, and sell them during bear markets. Here’s another gem from Buffet’s 1999 letter to shareholders:

It appears to us that many companies now making repurchases are overpaying departing shareholders at the expense of those who stay….I can’t help but feel that too often today’s repurchases are dictated by management’s desire to “show confidence” or be in fashion rather than by a desire to enhance per-share value.

Letter to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Inc – 1999

And companies who do buybacks to compensate for the exercise in stock options just make things worse:

Sometimes, too, companies say they are repurchasing shares to offset the shares issued when stock options granted at much lower prices are exercised. This “buy high, sell low” strategy is one many unfortunate investors have employed — but never intentionally! Managements, however, seem to follow this perverse activity very cheerfully.

(ibid)

In short, buybacks are losing you money, and overpaying for stocks, benefiting those who sell their shares at the expense of loyal shareholders. And why? All to pump the stock price that enables corporate executives to benefit from stock-based metrics like EPS, either directly through performance incentives, or indirectly through meeting analyst expectations.

Without Dividends, Buybacks Make no Sense

The only real benefit I can find in buybacks is that they increase the dividend per share, assuming that the payout ratio remains constant. Whether it would have been better to pay the dividend in the first place depends on the price at which the shares are repurchased, among other things, so I can’t say definitively whether it’s good or bad.

However, note that it again, comes down to the Gordon equation. A buyback only makes sense if it either:

- Increases the dividend yield

- Increases the growth of that yield

These things can happen with a buyback, but it’s not guaranteed. Certainly if a company like Berkshire is committed to never paying a dividend, then a buyback has no benefit.

Dividends are Never Cut as Much as the Price Falls

Yet another objection I hear is “Dividends are not guaranteed”. Well, this is investing, what did you expect? If you want guarantees, go invest in treasuries! Of course, dividends are not guaranteed, and no sensible person would ever make that claim. (Note, by the way, the number of strawmen that must be built up, only to tear them down righteously.)

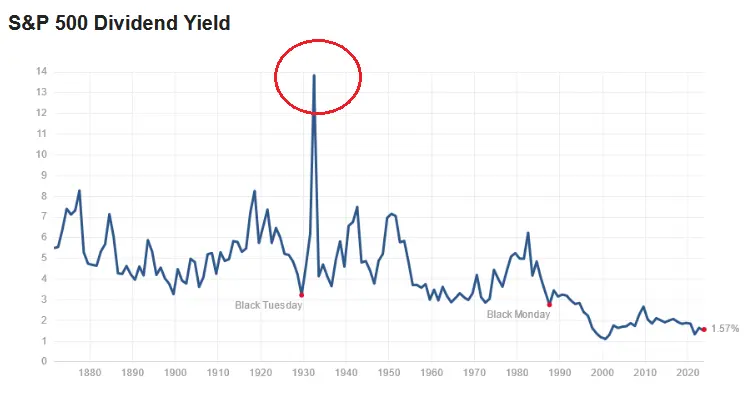

However, during times of crisis, companies never cut their dividends nearly as much as the price of their stocks falls. During the Great Depression, for example, stock prices fell by 89.2% at their deepest drawdown. My god, that makes the Great Financial Crash (GFC) look like child’s play. If there was ever a time for companies to slash their dividends down to the bone and avoid wasting money, this was it.

Instead, what did we see? During the Great Depression, dividend yields touched almost 14%! Incredible. Here’s a historical graph of the dividend yield of the S&P:

Source: https://www.multpl.com/s-p-500-dividend-yield

What does this mean? It means that while companies will cut their dividends when times are hard, they will not do so in proportion to the drop in their stock price. And this makes sense because dividends are not linked to the stock price. That is the whole point! Dividends are based on fundamentals, and just because the market panics, doesn’t mean that the fundamentals have deteriorated to the same extent, if at all.

Note how it was only during the dot-com bubble crash when the S&P was comprised of mainly overvalued, non-dividend paying tech stocks, that yields didn’t spike. If you need a further reminder to avoid tech stocks, this is it.

“Total Return” is NOT All that Matters

Yet another key argument of those claiming the irrelevance of dividends is that only total return is relevant. It doesn’t matter whether you get your return from dividends or capital gains. And selling your stock is the same as receiving a dividend, so capital gains and dividends are fungible. They are not claiming that dividends are useless, or that companies shouldn’t issue them. They are saying it doesn’t matter if a company issues dividends.

I’ve addressed two aspects of this separately. First, how dividends reduce company waste by extracting money from the hands of executives, and second, how capital gain is speculative growth, compared to dividend re-investment, which is proven growth. But I have another objection as well.

If Total Return is all That Matters, then Why not Bitcoin?

Most sensible investors will stay away from crypto. Hopefully, if you’re reading this, I don’t need to convince you that crypto is not an investment. Like gold, it is speculation. It generates no cashflow and its only selling point is that it appreciates in price.

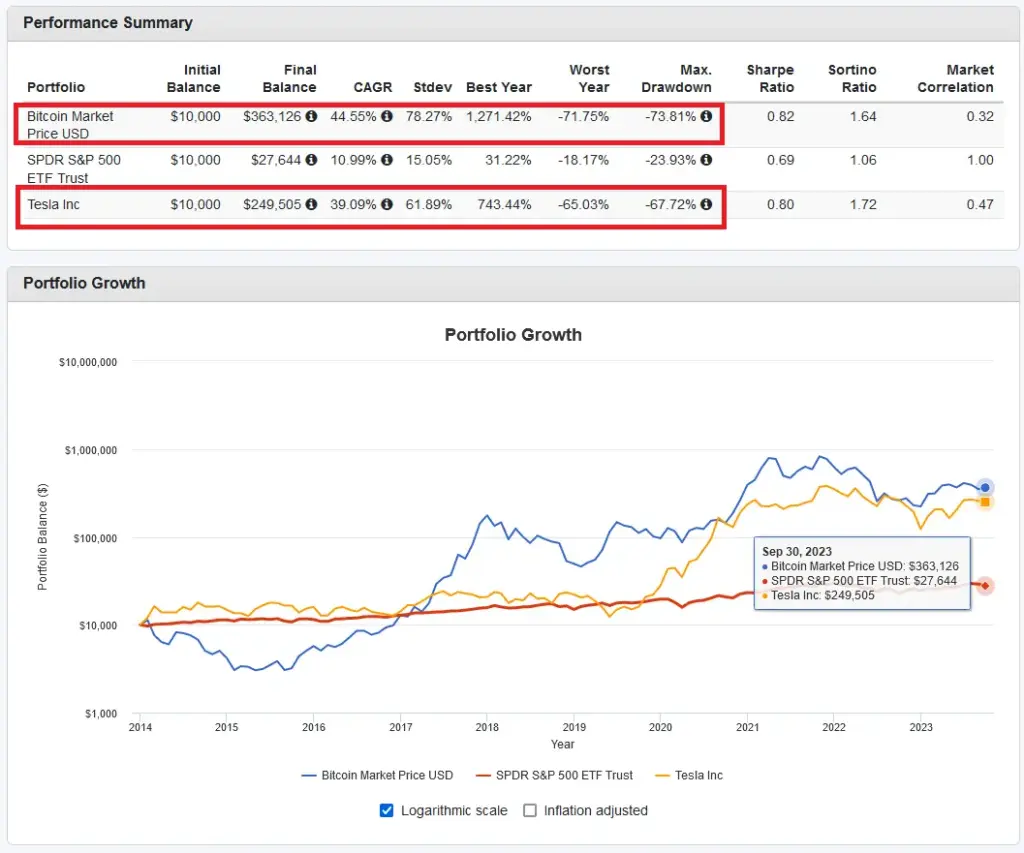

But the total returns are amazing, easily outstripping even Tesla, and knocking the pants off the S&P. Here, I’m using the Portfolio Visualizer Asset Allocation Backtest tool from 2014, and you can see how Bitcoin has performed:

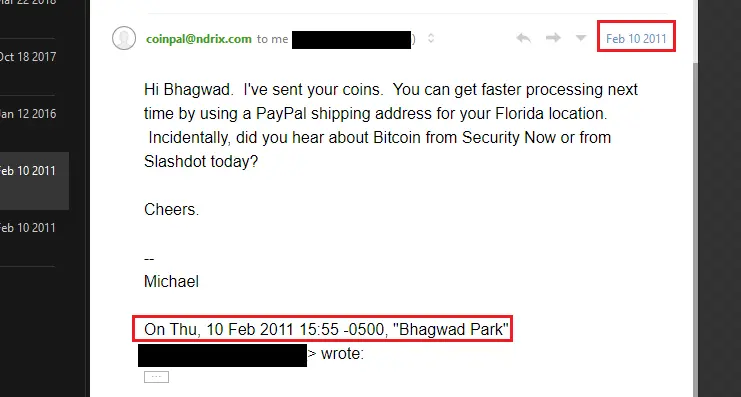

Over the past 10 years, Bitcoin has outperformed even Tesla by 5% annualized. Now, of course, I don’t recommend yolo’ing into Tesla, either, but look at Bitcoin’s total return! Actually, the chart understates Bitcoin’s return since it only starts from 2014. Do you know that in 2011, I bought 10 bitcoins for $1 each! Here’s an e-mail confirmation to prove it:

As of now, Bitcoin is selling for $28,000 each. For a purchase price of $1, I would have received an annualized return beyond anything Tesla or any company since then could have provided (I didn’t, because my coins were stolen in the Mt. Gox scandal). If I was a proponent of the “total returns are all that matter”, then Bitcoin would be classified as the most magnificent investment ever. But Bitcoin was, and remains, a gamble. A pure speculative play. It is not an investment. And why? Because, as I’ve repeated incessantly, it has no cashflow.

I’ll go one step further. Even if you knew for a fact that Bitcoin will zoom 10,000% in the next few years, it would still be a bad investment, for the simple reason that it’s not an “investment” at all. And that is the point I’m repeatedly making. There is a difference between investment and speculation, and the difference is cashflow. Those who focus on “total return” believe that price action is equally important, without considering that it is cashflow which makes something an investment. Bitcoin has a magnificent total return, and for all I know, it might well continue to have it decades from now. But it is not an investment.

Now I know what you’re thinking. “You can’t compare Bitcoin with a stock like Google, that has an insanely profitable company sitting behind it!”. Well, I have news for you :) .

Stocks are Not the Same as Companies

The most fundamental error you can make while picking stocks is to confuse stocks with the companies to which they belong. This is a category error. A company is a business. A stock is a financial instrument. These two are not the same thing.

A company like Google has heavy cashflow and is very valuable. Google stock, on the other hand, is dogshit. I value it at zero. This is because Google the company ≠ Google stock. But why do people make this mistake? Why confuse a financial instrument with a company? The reason is that people think that owning a share in a company means something.

Your Ownership in a Company Means Nothing

One of the biggest blindfolds pulled over the public’s eyes is the notion that the retail individual’s stock ownership has value. It does not. As a shareholder, there are only three ways in which you can extract value from a company:

- Dividends

- Liquidation of the company

- Taking control of the company and eating all its earnings yourself

Out of these three, dividends are the only way regular investors can extract money from the company and share in its profits. Liquidation or bankruptcy of the company is a terrible way to extract money because if the company’s being wound up, chances are that it’s falling apart and there’s almost nothing left, in which case, you as a shareholder will be among the last vultures who will get to pick at its carcass.

“But wait!”, you say. The value of Google stock can’t go below a certain value, because if it goes too low, then someone will realize it, just buy up all the shares and take the earnings for itself!

If only it worked that way.

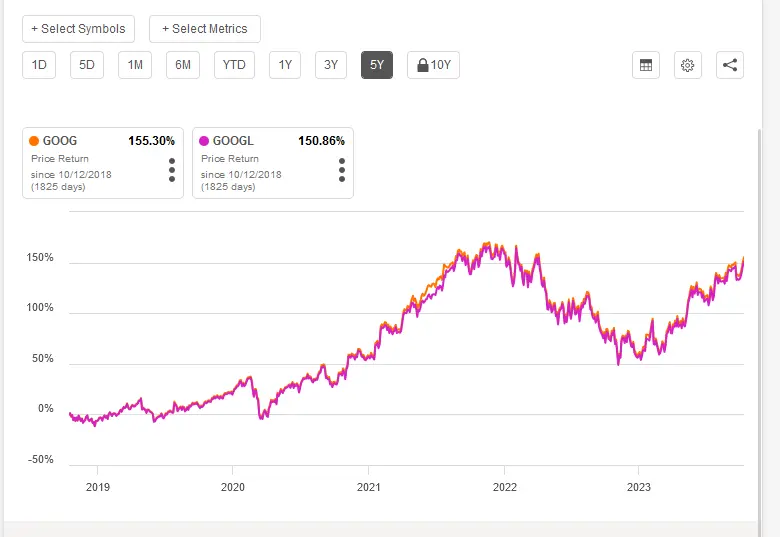

Voting Rights Mean Nothing. Exhibit: Google Class C Shares

For those who believe that ownership and voting rights mean something, allow me to introduce you to Google Class C shares, trading under the ticker symbol: GOOG.

These miraculous shares carry no voting rights! That’s right. For the generous price you pay for these most useless NFTs, you receive the following privileges:

- NO voting rights

- NO dividends

- The last on the ladder to receive anything when the company folds

GOOG is even more of a pathetic, transparent cash grab than its sister shares GOOGL, which at least have some voting rights – 1/10th the rights of Class B shares, to be precise. Class B shares are not traded on the public market. The real owners of Google don’t want you to have control over the company. So with all these negatives, GOOG should at least trade lower than Class B shares GOOGL, right?

Wrong.

Oh, mystery of mysteries, GOOG trades higher than GOOGL! The ultimate expression of shareholders being suckered into holding worthless financial instruments, all because they’re “backed by Google”. Here’s a price chart comparing the movement of GOOG vs GOOGL over the past five years:

Source: Seeking Alpha

At this point, there’s no difference between GOOG shares and the company issuing paper stickers, with a “backed by Google” caption on them. You get the same benefit, and the only hope you have is to offload the damn things to another sucker.

Hopefully, this little example will illustrate the fundamental truth – voting rights mean nothing and are worth nothing.

Berkshire Hathaway – the Elephant in the Room

The problem with quoting Buffet is that you can pull out something to support your view, whatever it is. Don’t like diversification? Buffet has argued that it’s a form of ignorance. Like diversification? Buffet has said that he wants his wife’s assets to be invested in a passive S&P fund. Like dividends? Buffet has plenty of quotes about dividends. Against dividends? Buffet has quotes about those too!

However, one thing is certain. Berkshire Hathaway does not pay dividends. And presumably, while Buffet is alive, it never will. It appears that it’s no coincidence that the corporate structures of Google and Berkshire are so similar in this regard. The co-founders of Google consulted Warren Buffet on how to take their company public without losing voting control. Neat!

I’m going to be honest here, and this will be an unpopular opinion amongst both those who favor dividends, as well as those who claim they’re irrelevant. Buffet is quite the hypocrite when it comes to dividends. As I said, there are plenty of Buffet quotes on both sides of the dividend argument. But I found this quote from the Berkshire Hathaway “Owner’s Manual” from 1999:

Intrinsic value can be defined simply: It is the discounted value of the cash that can be taken out of a business during its remaining life.

Berkshire Hathaway “Owner’s Manual” – 1999

Note the section in bold. Can be taken out of a business. This does NOT refer to selling your shares, which merely takes money out of someone else’s pocket. You can only take money out of a business in three ways:

- Dividends

- Liquidation

- Getting a cushy job at the company and doing no work

As a joke, I posted a question on Reddit about whether or not I could strongarm a company into paying me a salary for doing nothing if I owned a large number of shares. It didn’t go over well! But my point is that Buffet is a hypocrite because he makes it plain that, given a choice, he will never pay dividends, and will therefore, never allow cash to be taken out of Berkshire Hathaway.

Here’s another Buffet quote about how his favorite holding period is forever:

In fact, when we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favorite holding period is forever.

Chairman’s Letter – 1988

So wait a minute – if you’re supposed to never sell your stock, then how in hell does holding Berkshire Hathaway benefit you in any way? No dividends, the voting stock costs 100 times more than regular BRK.A shares, and you’re supposed to ideally never sell! Hey Warren, maybe you see a wee bit of contradiction here, huh?

Of course, this doesn’t stop Buffet from holding the shares of plenty of dividend-paying companies himself. More than once he’s talked about how thrilled he is that he’s receiving dividends from Coke – last year alone, Berkshire Hathaway received $704 million in dividends from Coke. But Berkshire itself will never share some of that money with its stockholders, no sir!

Berkshire Hathaway Keeps YOUR Earnings in Treasuries

The logic for retained earnings is that the company can re-invest them into the business and generate a higher rate of return than you could if they paid it out to you. And everyone agrees that Buffet is the master of this, the best investor of all time. Surely he must be using the massive earnings that his holdings generate to make investments and deals that only he can, right? What then, is Buffet doing sitting on $147 billion in cash? Out of this, $120 billion is sitting in short-term treasuries.

Now I know the answer. Despite everything I’ve written above, it’s hard to deny that Buffet, by sheer virtue of his longevity in the investing business easily counts as one of the greatest investors of all time. But you must admit, that even he is having trouble finding lucrative investment opportunities! This bolsters my thesis that easy revenue operating investments are not just lying around. If even Buffet – the man himself – has trouble putting his cash to use, then do you expect ordinary managers of companies to be able to use their earnings wisely by re-investing ALL the proceeds into their own business? Hell, if you’re going to hold it in treasuries, I could do that!

So I think Warren Buffet is doing a disservice to his investors by not paying out dividends.

We Need to EXTRACT Money From a Company – Not Sell Shares

As an investor, you want to receive a share of the company’s profits. This means at some point, you need to take money out of it. Selling your shares to someone else merely transfers money from them to you. Disposing of your shares doesn’t extract money from the firm. Yes, this will result in a taxation event, but there’s no getting around it.

So why is it so important to extract money from a company? The reason is that companies waste it without accountability.

How Companies Waste your Money: Why We Need Dividends

Surely, the capitalistic thought process goes, a company that tries to maximize profits would never waste money. What a beautiful thought, my sweet summer child! Step away from theory for a moment and look to reality. Perhaps you yourself have worked, at some point, in a large public company. Have you seen the debauched way in which money is thrown around for no reason? Have you seen millions being spent on consultants whose only output is a PowerPoint presentation that is jettisoned into a drawer, never to be seen again?

Just this year, we have heard reports of how tech companies hired workers to do nothing, for the flimsiest of reasons. As you’re reading this, you can probably think back to examples of waste that you have witnessed at your company. Waste that would put government spending to shame.

Here are some ways that companies waste your money when they don’t pay dividends.

Busting the Modigliani-Miller Theorem: the Agency Problem

The “gotcha” of the anti-dividend investor crowd is the Modigliani-Miller theorem. It’s like a magic card. All they have to do is to throw it down, cry “Modigliani-Miller Theorem!”, and they’re supposed to win the argument on the spot. It’s the ultimate shutting spell.

There’s just one problem. The assumptions of the Modigliani-Miller theorem are unrealistic.

Compared to the pristine world in which the theorem operates, there are two harsh realities:

- A firm’s investment policy is NOT independent of its dividend policy

- Company insiders get preferential treatment (including theft)

In other words, many company insiders hate dividends because they give a fair share of the profits to external shareholders on a pro-rata basis. In a paper in the Journal of Finance titled “Agency Problems and Dividend Policies around the World”, La Porta, Rafael and Lopez-de-Silanes, Florencio and Shleifer, Andrei and Vishny, Robert W make the following observations:

Failure to disgorge cash leads to its diversion, or waste, which is detrimental to outside shareholders’ interest.

La Porta, Rafael and Lopez-de-Silanes, Florencio and Shleifer, Andrei and Vishny, Robert W., Agency Problems and Dividend Policies Around the World (June 1998). NBER Working Paper No. w6594

Firms appear to pay out cash to investors because the opportunity to steal or misinvest it are in part limited by law, and because minority shareholders have enough power to extract it

How much clearer do you want this to be?

The authors make a strong distinction between “outside” shareholders and company executives. The implication is that the interests of the two don’t always align. Translation: Company executives are stealing your money, often legally, but sometimes even illegally.

Need more proof? Here’s a quote from everyone’s favorite value investing guru – Benjamin Graham, writing in the well-known book “Security Analysis” in 1934.

Whatever benefits a business benefits its owners, provided the benefit is not conferred upon the corporation at the expense of the shareholders . . . An inductive study would undoubtedly show that the earnings power of corporations does not in general expand proportionately with increases in accumulated surplus.

Graham, B. and Dodd, D. (1934). Security Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 437

The above quote was written in the context of investors talking about “a new era” almost 100 years ago. Plus ça change…

Companies Overestimate their Ability to Generate Additional Returns

Corporate executives appear to suffer from an exaggerated sense of their ability. It never ceases to amaze me when people confidently say “Retained earnings help a company invest in its own growth, and therefore it’s okay for a company to pay zero dividends.”. Wow. Just wow. As if amazing investing opportunities are lying by the wayside, just waiting for the company executives to scoop them up by the handful!

In a paper titled “Corporate Cash Reserves and Acquisitions”, Jarrad Harford notes the following:

Cash-rich firms are more likely than other firms to attempt acquisitions. Stock return evidence shows that acquisitions by cash-rich firms are value decreasing. Cash-rich bidders destroy seven cents in value for every excess dollar of cash reserves held. Cash-rich firms are more likely to make diversifying acquisitions and their targets are less likely to attract other bidders. Consistent with the stock return evidence, mergers in which the bidder is cash-rich are followed by abnormal declines in operating performance. Overall, the evidence supports the agency costs of free cash flow explanation for acquisitions by cash-rich firms.

Harford, Jarrad. “Corporate Cash Reserves and Acquisitions.” The Journal of Finance, vol. 54, no. 6, 1999, pp. 1969–97. Accessed 16 Oct. 2023.

The summary is that excess cash makes corporate executives careless. When under no pressure of accountability to shareholders via dividends, they make sub-optimal investments, overpay for acquisitions, and destroy massive amounts of shareholder value.

If you pay attention to tech acquisitions, you see this phenomenon in full view. How many companies has Google acquired, only for the staff of the acquired company to leave, and for nothing to emerge from the expensive acquisition? Any of you who have worked in close proximity to large corporations know what I’m talking about. I’ve seen it happen myself.

In another paper titled “The Cost of Diversity: The Diversification Discount and Inefficient Investment”, the authors Rajan, R., Servaes, H., & Zingales could not be more clear.

In a simple model of capital budgeting in a diversified firm where headquarters has limited power, we show that funds are allocated towards the most inefficient divisions. The distortion is greater the more diverse are the investment opportunities of the firm’s divisions.

Rajan, R., Servaes, H., & Zingales, L. (1998). The Cost of Diversity: The Diversification Discount and Inefficient Investment. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 6368. doi:10.3386/w6368

Even if they’re not actively trying to steal your money, company executives are – to put it mildly – incompetent. And what’s worse, they think they’re competent!

Human Managers Waste Money to Cover Their Asses

If you’ve worked in large companies, you know exactly what scams “management consultants” are. The YouTube channel “How Money Works” has an excellent video titled “How America Got Hooked On Useless Corporate Consulting”. If you don’t know about the gargantuan waste that happens when companies hire consultants, be prepared to feel sick.

But it’s not just YouTube videos that talk about this. There’s plenty of academic research to back this up. Managers hire consultants because they don’t want to take the flak for tough decisions. They always want to be able to say “Look, I even hired the top consulting firm and they showed me the data!”. Buried in all this is that consulting firms often simply confirm the biases of the person who hired them, since, you know – that’s who hired them. Companies will often spend hundreds of thousands and even millions of dollars on consultants to generate a PowerPoint presentation that they’ll throw into a drawer and will never look at again.

In the book “The Big Con: How the Consulting Industry Weakens Our Businesses, Infantilizes Our Governments, and Warps Our Economies”, Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington peel off the veneer of respectability that hiring a consultant offers. Martin G. Moore has also talked about how you’re often no better off than when you started after hiring a consultant. There’s a lot more literature about the inefficacy of consultants and how they waste mammoth amounts of money.

So what does this have to do with dividends? Simply put, dividends are money that the company can’t waste – for example, on consultants. The theme is the same. Take money away from companies before they can waste it!

Managers Waste Money in “Empire Building”

Another reason why companies waste money is rooted in human nature. Managers like to feel powerful, so they amass larger and larger teams, gathering more manpower, prestige, and power. The show “Yes Minister” illustrated this perfectly when Humphrey justified massive bureaucracy in these terms:

‘We want all responsibilities, so long as they mean extra staff and bigger budgets. It is the breadth of our responsibilities that makes us important — makes you important, Minister. If you want to see vast buildings, huge staff and massive budgets. what do you conclude?’ ‘Bureaucracy,’ I said. Apparently I’d missed the point. ‘No, Minister, you conclude that at the summit there must be men of great stature and dignity who hold the world in their hands and tread the earth like princes.’

(The Complete Yes Minister, p. 475)

This kind of thing is not limited to government. Any time you have human beings in charge of resources, they’re going to use it to create mini-fiefdoms. Surely you’ve seen this at work in your own organization? People with a god complex, who don’t give a f**k about whether or not the company makes profits, but just want to aggrandize themselves. It’s human nature, and there’s no point trying to fight it. Public or private makes no difference.

Bottom line: All of the above illustrates one of the most important reasons for companies to issue dividends. To remove money from the hands of executives. The less money they have, the less money they can waste.

Dividend Growth: The Factor Investing Distraction

We’ve known for a long while that dividend growers, at the very least, keep up with broad market returns, if not beating them outright. There’s ample evidence indicating that investing in dividend growth companies is an excellent strategy. In fact, Ben Felix – the creator of the infamous “Irrelevance of Dividends” video created another video acknowledging that investing in dividend growers actually outperforms the market.

Now theoretically, the outperformance of dividend growers comes down to what we call “factor investing”. There are a few additional risk factors that generate excess returns to compensate for that risk. Depending on the model, there can be three, five, or even more factors. But the most commonly accepted ones are:

- Market risk

- Small caps

- Value companies

- Profitability

- Conservative investments

The details are unimportant, but the gist of the explanation of why dividend growers outperform broad market index funds is that these companies indirectly target the five factors of investing. So, according to this school of thought, it’s not the dividends themselves that are driving the returns, but the underlying factors.

Following the above logic, targeting the dividend growers themselves is inefficient because it reduces your diversification, and generates a higher tax burden to boot. That makes sense, right? Not quite.

It’s Not Easy to Target Metrics like “Value”

Dividends are easy to measure. A factor like “value”, on the other hand, is notoriously hard to pin down. Decades ago, value was simply measured as the P/B ratio. Then we started to move to P/E ratios. But these days, identifying a “value” company is harder than ever. Businesses are more complex, and so many of their assets are intangible and a regular “book” value is all but impossible to compute.

In addition, changes to accounting practices can constantly change whether a given metric represents “value” or “profitability”. If an accounting practice changes to allow R&D expenses to be capitalized rather than expensed immediately, then the traditional measures of profitability will change for certain companies. Being able to analyze the impact of these changes, staying abreast of these changes, and making the connection between the two to reclassify what is a “value” company can be incredibly hard, if not impossible. Now extend that to ETFs that target thousands of companies at once, and it’s just a mess. Not to mention that companies can fudge their data, and some funds hold stocks in multiple countries, making it utterly unrealistic to track the accounting laws of each of them.

Dividends cut through this mess. They represent actual, tangible money returned to their investors. With a few quality screens like monitoring the payout ratio, and assessing the level of indebtedness of a company, you have a highly efficient proxy for five factors. Just make sure you’re diversified and not paying excessive fees.

As investors, we are not idealists. We do what works. Whether or not dividend growth is the “real” driver of returns is irrelevant to us. If it works, it works.

The “Anti-Dividends” Fanaticism

There’s a certain religious fervor amongst those who are vehemently against dividends. You can see it in the way they crusade against dividend investing, entirely out of proportion to the perceived harm. Even going by their logic, the worst thing you can say about dividend investing is that it’s slightly suboptimal. You’re not throwing your money away on penny stocks, gambling, or betting it all on crypto. You’re not leveraging yourself to buy stocks on margin, or betting it all on high-growth tech companies.

Compared to this, you never see dividend investors creating videos lambasting growth stocks, or tweeting provocatively about how those who invest without dividends are gullible and misinformed. Instead, dividend investors pretty much quietly enjoy their portfolio and their dividends. They like to talk and compare with each other of course, but there’s no hostility or animosity towards the larger non-dividend crowd.

I’ve concluded that these posts and videos are just cheap rage bait. If you insult a set of people, you’re going to get clicks and drive up engagement. The Youtubers and Twitter (yes Twitter, not X, lol) influencers have figured out a cheap way to get attention to themselves, and it works.

Nonetheless, Some of them Have Good Intentions

Despite the above, I believe some of the “anti-dividend” crowd have good intentions, though it can be tempting to kill two birds with one stone and get clicks in addition to the genuine motivation to educate. I take it on a case-by-case basis. I think Ben Felix, for example, genuinely has good intentions while creating his videos, but it’s hard to deny that his “irrelevance of dividends” crusade has elements of clickbait, considering there are plenty of other far more problematic investing strategies out there. Instead, he’s made no less than three videos on dividend investing alone (so far), so you can see where I’m coming from.

Dividends are Better from a Behavioral Standpoint

Geeking out over the most optimized portfolio for total returns is fun. But the stark truth is that failure or success in investing is more about behavior and less about who has the best portfolio. A suboptimal portfolio that you can stick to in times of panic will always beat out an “optimal” portfolio in the long term. Most negative outcomes in retail investing are due to a handful of behavioral mistakes that can often wipe out decades of good behavior.

There’s a stark difference in the mindset of dividend investors vs most people who invest in the stock market. Namely that the former is focused on long-term goals. Dividend investors like the feeling of watching their income slowly grow. Several of them have intermediate goals like having their dividends purchase a discrete, additional share each time. In his paper on Balancing Long-Term Goals versus Short-Term Risks, Ronald J. M. van Loon has this to say:

These are situations where it is not only the end goal that matters, but also the journey toward it…The addition of an intrahorizon loss constraint can lead to meaningfully different investment behavior.

van Loon, Ronald J. M.. “Balancing Long-Term Goals versus Short-Term Risks.” Journal of Investing (2022).

And this is what dividend investing provides. The “Irrelevance of Dividends” crowd holds a very idealistic view of the world where we’re all rational beings, and where we’re just supposed to ignore the emotional parts of investing, treating them as inconveniences, and having blind faith in our ability to shut them out. The truth is that when shit hits the fan, these self-professed rational people will panic like everyone else.

The psychologist Jonathan Haidt, in his book “The Happiness Hypothesis”, talks about your emotional mind as being the elephant, while you, the intellect, are the rider. As the rider, you have only a limited amount of control of your elephant, and the more you fight against it, the more it drains you. You think you’re in charge, but you’re not. We constantly underestimate our power to control our impulses.

“It’s hard for the controlled system to beat the automatic system by willpower alone; like a tired muscle, the former soon wears down and caves in, but the latter runs automatically, effortlessly, and endlessly.”

Haidt, J. (2006). The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. Basic Books.

You can’t fight your impulses for decades. And god help you if you enter a bear market lasting over a decade like we did from 1966-1982. No one has the mental strength to hold out against their nature for sixteen years. If you head over to the /r/Bogleheads subreddit, you’ll see people right now complaining that their investments haven’t grown in the past two years. And that’s a subreddit dedicated to telling people to invest for 30 years or more!

The truth is, you need to work with your nature, not against it. You need intermediate-term goals if you’re going to stay the course, and you particularly need that help in times of distress. Dividends give you those intermediate goals and will help you outperform those who don’t have them.

Working WITH “Mental Accounting”, Not Against it

Another thunderbolt thrown against dividend investors is that they’re engaging in “mental accounting”. This is our tendency to treat money as non-fungible and view dividends as a separate income stream rather than a subtraction from our capital. While I’ve noted my objections to this logic above, the flaw here is thinking that we can escape mental accounting in the first place.

The truth is that we humans use mental accounting all the time. Even the most fervent “dividend irrelevance” adherents adopt mental accounting. One instance of mental accounting, for example, is called “Price Anchoring” – when you base a decision to purchase something based on the listed price instead of its inherent objective value. Let’s say tomorrow Google drops by 50%. The same people who accuse dividend investors of indulging in “mental accounting” will jump at the opportunity to jump at “cheap” Google shares. Have such people done the fundamental analysis of Google themselves and concluded that its current share price is cheap? Of course not! They’re indulging in mental accounting.

Whether it’s freely spending a windfall, or gambling more recklessly once you’ve won a bit of money, “mental accounting” is deeply baked into human nature. I’m sure you’ve done it several times within the past week, so if you find yourself chastising dividend investors for “mental accounting”, I suggest you take a long, hard look in the mirror.

The moral of the story is that we must work with our nature, not against it. If we have a strong tendency to engage in mental accounting, then we must leverage that and turn it into a strength, instead of a weakness. Dividends help us stay the course because of mental accounting, not despite it.

With Dividends Stock Price is Irrelevant

I bought a house last month all in cash. I later posted a CMV on Reddit saying that I don’t benefit from my house appreciating in value. The reason is that even for buying a house, I used the Gordon equation and calculated my implied returns to be from anywhere between 6-8%, given the savings I get on rent. That’s because my house has an intrinsic value, and I don’t care for how much it sells. Sure, it helps that I live in the best condo building in Toronto, but even that can be accounted for with higher rents and cashflows.

When you invest using the Gordon equation with dividends, you stop caring about what the stock price is and the number shown on your brokerage account. That’s because you are already getting the benefit of the asset. In fact, you probably don’t want your stock to appreciate. The reason is that lower stock prices juice your returns and allow you to purchase even more shares with your dividends than before.

As a dividend investor, I get a warm feeling when I see my stocks go down in value because I know that I’ll be able to purchase more of them with my dividends. Remember – as shown above, even during recessions, dividends are never cut anywhere near as much as the stock price falls. So even with lower dividends, you’re getting a real steal on the re-investment whenever the market falls. The annoying part is if the market goes up when you need to re-invest the dividends!

Conclusion

I’ve tried to be as thorough in my analysis of every aspect of dividend investing. I few months ago, I’d written a Reddit post titled “In defense of dividends” in response to another post. This blog post is an attempt to flesh out many of the points I made in that post, and I’ve added several new sections and thoughts and attempted to support my arguments with citations and data wherever possible. I hope you found this interesting!

There are share repurchases, many companies prefer to give money to investors through that way instead of dividends for tax reasons.

In reply to Luis

Thanks for pointing that out. I added a new section on share repurchases:

https://www.bhagwad.com/blog/2023/personal/financial-matters/dividends-are-not-irrelevant-when-a-stock-becomes-an-nft.html/#why-stock-buybacks-arent-good-enough

You should think about turning this into a dividend based E-Book. Thank you for the time you spent writing this!

In reply to Jon

Thank you for your kind words :)

What a high value post. Thanks for the effort. PDF this at a minimum as a lead gen for the course you need to be offering.

In reply to David

Thanks – no need for a course, or anything, since a lot of this is just common sense!

Excellent post; it really got me thinking. My intuition agrees with you, so I went back to look at what people had said on your Reddit thread. In this post, perhaps in response to the Reddit comments, you rightfully point out that buying stock that doesn’t return a dividend is nothing more than speculation.

The issue, I think, is that you aren’t giving speculation its due diligence. Lots of people have made lots of money through speculation and lots of people will continue to make money through speculation. I don’t think you’ve sufficiently defended the argument that investments (as you’ve defined them) are better than speculations.

The reality is, people can sell Google stock. People can make money by speculating on stocks. You haven’t done a good enough job telling me why I shouldn’t try that. What is the argument against buying Bitcoin? The best argument against speculation that I see in this post is that it’s risky; you explicitly call Bitcoin a gamble and imply that Google stock is similar.

But risk can be worthwhile; it must be, to ever justify buying stocks over bonds. In that scenario, people acknowledge that the risk is low enough to justify the potential to increase returns. It’s plausible that some speculation, such as buying Google stock today and holding it for 10+ years, is low enough risk to justify the potential to get a greater return than dividend investing provides. In that scenario, what is the argument against buying Google stock?

You went so far as to say that even if Bitcoin wasn’t risky, and you knew it would go up 100x in the next 10 years, it would still be speculation in your eyes. But who cares that it’s speculation? I’d be buying for sure if I had that kind of foresight. I wouldn’t care that it doesn’t cashflow. After 10 years I could sell my Bitcoin, buy dividend stocks, and have more in cashflow than if I’d focused on cashflow from day one.

Ultimately, it seems like the post assumes that cashflow for cashflow’s sake is worthwhile. But for most young people, the end goal is not cashflow, but wealth building. Cash flow is only a means towards wealth building, and it’s certainly not the only means. Only after people have “enough” wealth do they switch from prioritizing wealth building to prioritizing cash flow. In other words, I think you’re prioritizing cash flow but arguing with people that are prioritizing wealth building.

I really enjoyed the article and I’m definitely inspired by your financial journey. Hopefully I stumble across another one of your posts in the future.

In reply to Daryl

Thanks for your thoughtful comment :) . You make some interesting points!